NEAR

Greetings!

Welcome to the NEAR Protocol Book. A collection of tutorials that aim to simplify the learning process and helps get started with NEAR. Whether you are a developer, entrepreneur, or enthusiast, this guide will provide you with a comprehensive introduction to the NEAR ecosystem.

Table of content

Here are some of the topics that we will cover in this repository:

- Introduction to NEAR

- NEAR Architecture

- Economy

- Security

- Blockchain Operating System (BOS)

- Summary

- Resources

Introduction to NEAR

NEAR is a layer one, sharded, proof-of-stake blockchain. designed to offers fast and scalable solutions to users and developers alike. NEAR aims to make it easier for developers to build decentralized applications.

Why NEAR:

- Uses human-readable accounts

- Fast and cheep transactions

- Scalable. Thanks to its sharding

- Possess a simple yet rich system of Access Keys to handle account permissions

- Supports multiple programming languages, making it accessible to a wide range of developers

NEAR Architecture

NEAR is a stateful blockchain that maintains a global state updated by transactions. The state is stored as a trie. In NEAR, users and applications have access to the global state.

NEAR uses a sharding technique called Nightshade to distribute it's network.

Key roles in the NEAR blockchain ecosystem include:

- Validators – provides compute, storage and security in the network in return for rewards from the protocol

- Developers – build profitable applications, powered by underlying infrastructure of the protocol

- Users – users of applications, and platform itself, are driven by getting value out of these interaction

- Token Holders – holders of protocol (native) token, either for later usage or to provide liquidity

- Protocol Governance Body – entity responsible for development and governance of the network. This can be a DAO and/or non-profit foundation

Consensus

NEAR uses Thresholded Proof-of-Stake consensus mechanism.

Transactions are grouped into blocks. Blocks are grouped into epochs. In a chain, the set of blocks that belongs to some epoch forms a contiguous range. Each epoch is associated with a set of block producers responsible for validating blocks within that epoch.

The information for an epoch is determined by the last block.

Therefore, if two chains share the last block of some epoch, they will have the same set and the same assignment for the next two epochs, but not necessarily for any epoch after that.

The consensus protocol defines a notion of finality, which helps ensure that transactions in a final block (and preceding blocks) are irreversible.

In NEAR a consensus node (block producer) doesn’t validate an entire block, but rather specified chunks of each block.

NEAR relies on its own variant of consensus algorithm known as Doomslug.

Doomslug ensures that a block is irreversible unless at least one participant is slashed, providing practical finality.

Anyone can become a block producer and/or validator on NEAR as long as they have NEAR tokens to lock as collateral.

Thresholded Proof-of-Stake

In PoS systems, nodes participate in decisions proportionally to the amount of money they have. One common implementation of PoS is Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS), where the network votes for delegates who maintain the network and make decisions on behalf of other members. However, this can lead to centralization and a small number of nodes controlling network maintenance medium.com.

TPoS aims to address these issues by using an election mechanism that deterministically selects a large number of participants for network maintenance, thereby increasing decentralization and security. This method is similar to an auction, where people bid for a fixed number of items, and the top N bids win while receiving a number of items proportional to the size of their bids medium.com.

Doomslug

At the beginning of every epoch (1/2 day) the set of largest stake-weighted participants on the network are selected.

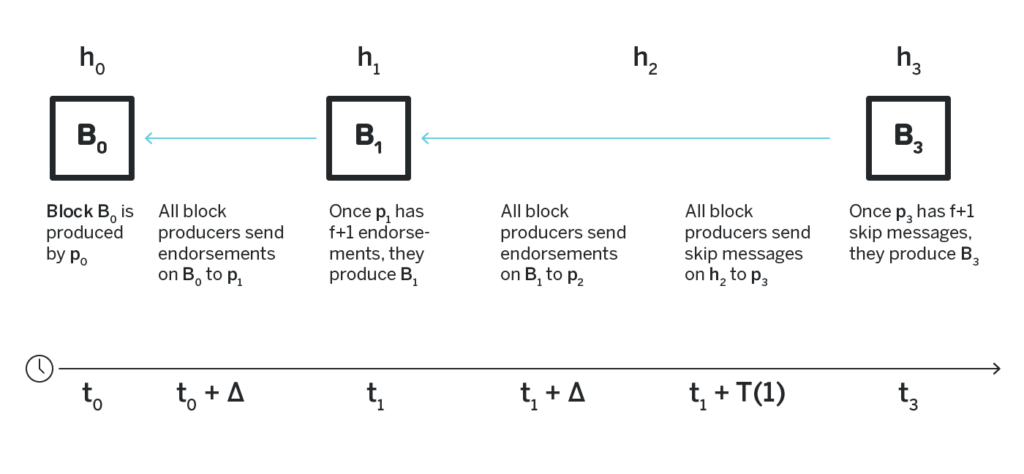

In short, Doomslug works by having a set of participants take turns to produce and broadcast blocks. Once a block at height h is received by other participants, they send endorsements on such a block to the participant assigned to the next height h+1. If after some predetermined time the participant assigned to h+1 hasn’t produced a block, the participants who sent an endorsement to her send another message to the participant assigned to h+2 indicating that they suggest skipping the block at h+1.

NEAR does not have explicit slashing for availability (liveness). However, if a validator is not responsive enough at every epoch (fulfilling with minimum threshold of chunks), they will drop out of the consensus set and lose the rewards from the epoch. Once that happens, the validator must re-stake the tokens.

What refers to as practical finality, or doomslug finality is that a block produced by Doomslug is irreversible unless at least one participant is slashed. Doomslug also has a nice property that it continues producing and finalizing blocks for as long as just over half of all the participants are online and honest

Accounts

Every account at NEAR belongs to some shard. All the information related to this account also belongs to the same shard. The information includes:

- Balance

- Locked balance (for staking)

- Code of the contract

- Key-value storage of the contract

- All Access Keys

- Postponed ActionReceipts

- Received DataReceipts

Every NEAR account is identified by a specific address. Based on their name, two types of accounts can be distinguished:

Named accounts, with human readable names such asalice.near.Implicit accounts, referred by 64 chars (e.g.98793cd91a3f870fb126f662858[...]).

Access Keys

NEAR accounts can have multiple keys, each with their own set of permissions. Access Keys are similar to OAuths, enabling you to grant limited access over your account to third-parties. Full Access keys have full control of an account, similar to having administrator privileges on your operating system

Full Access Keys

As the name suggests, FullAccess keys have full control of an account, similar to having administrator privileges on your operating system.

- Create immediate sub-accounts

- Delete your account (but not sub-accounts, since they have their own keys)

- Add or remove Access Keys

- Deploy a smart contract in the account

- Call methods on any contract (yours or others)

- Transfer NEAR Ⓝ

Function Call Keys

FunctionCall keys only have permission to call non-payable methods on contracts, i.e. methods that do not require you to attach NEAR Ⓝ.

FunctionCall keys are defined by three attributes:

receiver_id: The contract which the key allows to call. No other contract can be called using this keymethod_names: The contract's methods the key allows to call (Optional). If omitted, all methods may be calledallowance: The amount of Ⓝ allowed to spend on gas (Optional). If omitted, the key will only be allowed to call view methods (read-only)

Function Call keys main purpose is to be handed to apps, so they can make contract calls in your name

Locked Accounts

If you remove all keys from an account, then the account will become locked, meaning that no external actor can perform transactions in the account's name.

In practice, this means that only the account's smart contract can transfer assets, create sub-accounts, or update its own code.

Locking an account is very useful when one wants to deploy a contract, and let the community be assured that only the contract is in control of the account.

Storage

Storing data on the blockchain has a long-playing role. Networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum misprice storage by only allocating reward to miners who mined specific transactions instead of future miners who will need to continue storing this data while they are mining.

In NEAR, Ⓝ also represents the right to store some amount of data. Token holders have the right to occupy some amount of the blockchain’s overall space.

For example, if Alice has a balance of 1 Ⓝ, she can store roughly 10 kilobytes on her account. This means that users need to maintain a fraction of Ⓝ as a minimum balance if they want to have their account, similar to how checking accounts in banks require a minimum balance.

This allows contracts which are maintaining important state to pay to Validators proportionally to the amount of data they are securing. For example, an important contract of the stable coin that would maintain the balances of millions of users will accordingly need to have a reserve of Ⓝ to cover the amount of storage it will require on the blockchain.

Blocks

A block includes one chunk for each shard, and it is the chunks which include the transactions that were executed for its associated shard.

Near is a permissionless blockchain, so anyone (with sufficient stake) can become a chunk-only producer, or a block producer

Transactions and Receipts

Transactions are created outside the Near Protocol node, by the user who sends them via RPC or network communication. Receipts are created by the runtime from transactions or as the result of processing other receipts.

Trie

Near Protocol is a stateful blockchain. there is a state associated with each account and the user actions performed through transactions mutate that state. The state then is stored as a trie

Near partitions the trie between the shards to distribute the load. It synchronizes the trie between the nodes, and eventually it is responsible for maintaining the consistency of the trie between the nodes through its consensus mechanism and other game-theoretic methods

Nightshade

Nightshade is the implementation and design of NEAR’s sharded architecture.

Nightshade splits the work of processing transactions and states across many participats (shards) to ensure the network can scale as it grows in users and demand. It calls State Sharding.

Each shard contains its own data and can process transactions independently of the others.

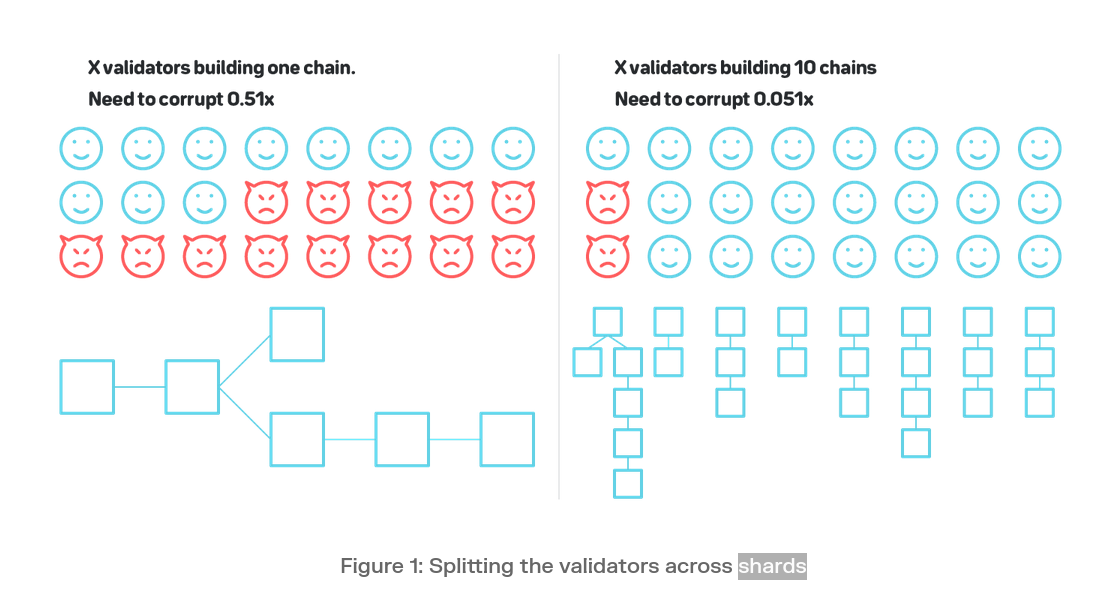

Practically, under State Sharding the nodes in each shard are building their own blockchain that contains transactions that affect only the local part of the global state that is assigned to that shard. Therefore, the validators in the shard only need to store their local part of the global state and only execute, and as such only relay, transactions that affect their part of the state

Nightshade also introduces Dynamic Resharding which allows the network to dynamically split and merge shards based on demand and resource utilization.

Picture below shows a chain shared to 10. also shows how many corrupted node is needed to corrupt a shard.

Beacon Chain is a layer-1 blockchain that coordinates the activities of the shard chains.

Beacon chain do some bookkeeping computation, such as assigning validators to shards (randomness), or snapshotting shard chain blocks, that is proportional to the number of shards in the system. Since the Beacon chain is itself a single blockchain, with computation bounded by the computational capabilities of nodes operating it, the number of shards is naturally limited

nodes in the blockchain perform three important tasks: not only do they 1) process transactions, they also 2) relay validated transactions and completed blocks to other nodes and 3) store the state and the history of the entire network ledge

Smart Contracts

NEAR is considered as a smart contract platform, developers can build applications that interact with each other on the NEAR blockchain.

Smart contracts are pieces of executable code stored in the account's state that have their own storage, and perform transactions in the account's name.

NEAR smart contract are a bit different from ethereum.

If you’re familiar with Ethereum’s pricing model, you may know that, like NEAR, the protocol charges a fee (called gas) for each transaction. Unlike NEAR, Ethereum's gas fee accounts for the amount of data stored via that transaction. This essentially means that anyone can pay once to store permanent data on-chain.

But how NEAR works:

Let's walk through an example:

- You launch a guest book app, deploying your app's smart contract to the account

example.near - Visitors to your app can add messages to the guest book. This means your users will, by default, pay a small gas fee to send their message to your contract.

- When such a call comes in,

NEARwill check thatexample.nearhas aenough balancethat it can stake an amount to cover thenew storageneeds. If it does not, the transactionwill fail.

btw, you can remove data to unstake some tokens.

Each NEAR account can only hold 1 smart contract. You can always re-deploy a smart contract on an account.

For applications where users should be able to organize multiple contracts you can create subaccounts whose master account is the user account

Smart contracts can earn fees. by default, 30% of the gas fees are paid to the smart contract owner.

Token Loss

Token loss is possible under multiple scenarios. These scenarios can be grouped into a few related classes:

- Improper key management

- Refunding deleted accounts

- Failed function calls in batches

Token loss in Refunding deleted accounts scenario is a issue on NEAR Protocol that need to be addressed.

It is because of the NEAR Nightshade sharding algorithm, which generate receipts for transactions' actions.

The first problem with Nightshade is that now we have Two concepts instead of one: transactions AND receipts.

In NEAR, transactions are not changing the state of the shard much, but receipts are. receipts will be executed in the receiver shard. They also will be included in the next block.

And now it is not easy to NOT execute the original transaction (already mined in the last block) which could prevent the token loss. now that the transaction is executed (and account is deleted) we have to execute the receipts (including the refund receipt).

Transactions

NEAR is asynchronous by design. While it opens a wide range of possibilities for smart contracts implementations, it may also add to confusion among beginners and newcomers from other blockchain platforms. Transactions in NEAR may contain actions that do asynchronous work, in such cases keep in mind the possible outcomes of success or failure of the transaction. For example, if a transaction contains a cross-contract call, it may be marked as successful, but the other contract execution might fail. This article covers possible scenarios for this.

A transaction is the smallest unit of work that can be assigned to the network. Work in this case means compute (executing a function) or storage (reading/writing data). A transaction is composed of one or more Actions. A transaction with more than one action is referred to as a batch transaction. Since transactions are the smallest units of work, they are also atomic, but again, asynchronous actions do not necessarily cascade their success or failure the whole transaction.

There is also a concept of Receipt, which is either request to apply an Action or result of the Action. All cross-contract communication is done through receipts. An action may result in one or more receipts. The Blockchain may be seen as a series of Transactions, but it's also a series of Receipts.

A Transaction is a collection of Actions that describe what should be done at the destination (the receiver account).

Each Transaction is augmented with critical information about its:

- origin (cryptographically signed by

signer) - destination or intention (sent or applied to

receiver) - recency (

block_hashfrom recent block within acceptable limits - 1 epoch) - uniqueness (

noncemust be unique for a givensignerAccessKey)

An Action is a composable unit of operation that, together with zero or more other Actions, defines a sensible Transaction. There are currently 8 supported Action types:

FunctionCallto invoke a method on a contract (and optionally attach a budget for compute and storage)Transferto move tokens from between accountsDeployContractto deploy a contractCreateAccountto make a new account (for a person, contract, refrigerator, etc.)DeleteAccountto delete an account (and transfer the balance to a beneficiary account)AddKeyto add a key to an account (eitherFullAccessorFunctionCallaccess)DeleteKeyto delete an existing key from an accountStaketo express interest in becoming a validator at the next available opportunity

A Receipt is the only actionable object in the system. Therefore, when we talk about processing a transaction on the NEAR platform, this eventually means applying receipts at some point

There are several ways of creating Receipts:

- issuing a

Transaction - returning a promise (related to cross-contract calls)

- issuing a refund

Due to NEAR asynchronous design and Nightshade algorithm. Transactions (or receipts) are not being processed in one block. instead they create receipts which will be executed in the next block(s), and also those receipts may generate other receipt, that will be included and executed in the next block(s).

This mechanism raises some problems like Token Loss that is because the deleting account action and refund or transfer token actions are not being executed in one block and therefore can not be prevented.

Or a failed action (while the transaction itself was successful and other actions actually got executed)

Due to NEAR asynchronous design and Nightshade algorithm. Transactions are not being processed in one block. instead they create receipts which will be executed in the next block(s), and also those receipts may generate other receipt, that will be included and executed in the next block(s).

This mechanism raises some problems like Token Loss that is because the deleting account action and refund or transfer token actions are not being executed in one block and therefore can not be prevented.

Or a failed action (while the transaction itself was successful and other actions actually got executed)

Economy

Smart Contracts Economy

NEAR leverages token economics in a unique way that empowers both creators and developers, who for example earn 30% of the fees their contracts generate, while network participants earn rewards for validating transactions or providing storage.

Storage Economy

When you deploy a smart contract to NEAR, you pay for the storage that this contract requires using a mechanism called storage staking.

In storage staking (sometimes called state staking), the account that owns a smart contract must stake (or lock) tokens according to the amount of data stored in that smart contract, effectively reducing the balance of the contract's account.

Indexing node will keep all data forever, but validating nodes (that is, the nodes run by most validators in the network) do not. Smart contracts can provide ways to delete data, and this data will be purged from most nodes in the network within a few epochs.

Validators

Validator selection is done via an auction mechanism. To become a validator, the node must send a signed transaction which contains information about the amount they want to stake and a new public key that blocks will be signed with.

Security

Blockchain Operating System (BOS)

BOS is a decentralized platfrom that aims to make it easier for developers to build and deploy decentralized applications (dApps). It is built on top of the NEAR Protocol.

BOS provides a number of features that make it a powerful platform for dApp development, including:

- A simple and easy-to-use development environment

- A wide range of tools and libraries for building dApps

- A decentralized governance system that allows the community to shape the future of BOS

- A commitment to security and scalability

Summary

Near Blockchain like many other blockchain has it is own cons and pros. here is a summary of these cons and pros.

Pros

- Account Names

- Having Storage Space By Staking

Cons

- Complex Design

- Asynchronous Desgin

- Token Loss

Resources

- NEAR Website: https://www.near.org

- NEAR Docs: https://docs.near.org/

- NEAR Learn: https://pages.near.org/learn/

- NEAR Learn More: https://pages.near.org/learn/learn-more/

- NEAR pages: https://pages.near.org/

- NEAR whitepaper https://near.org/papers/whitepaper/

- NEAR Whitepaper, Ebook Version https://near.org/whitepaper

- NEAR YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@NEARProtocol

- NEAR Spec, Nomicon: https://nomicon.io/

- NEAR Medium: https://medium.com/nearprotocol/

- NEAR Examples: https://github.com/near-examples

- NEAR NEPs: https://github.com/near/NEPs

- NEAR Indexers: https://near-indexers.io/docs/intro

- Doomslug: https://near.org/blog/doomslug-comparison/

- Blockchain Acceleration Foundation: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL0cPWYDSqQ29yI57TUbKwqU8KbYv4MEX5

- Learnnear club: https://learnnear.club/

- Figment: https://learn.figment.io/protocols/near